You are loved, you are honored, you are cherished.

You belong here.

Every Sunday we begin our worship with a prayer, asking that our hearts may be open to all those who cross our threshold and that we may welcome each person in the spirit of God's love. At the heart of our community is this welcoming spirit of love and acceptance for all God's children. Because we know that we have been made welcome by Jesus, that we have been drawn in an embraced by the love of God.

Want to get involved?

What's On?

If you're exploring St. Mary's, or just looking for the latest news, services, and events, you can find them here.

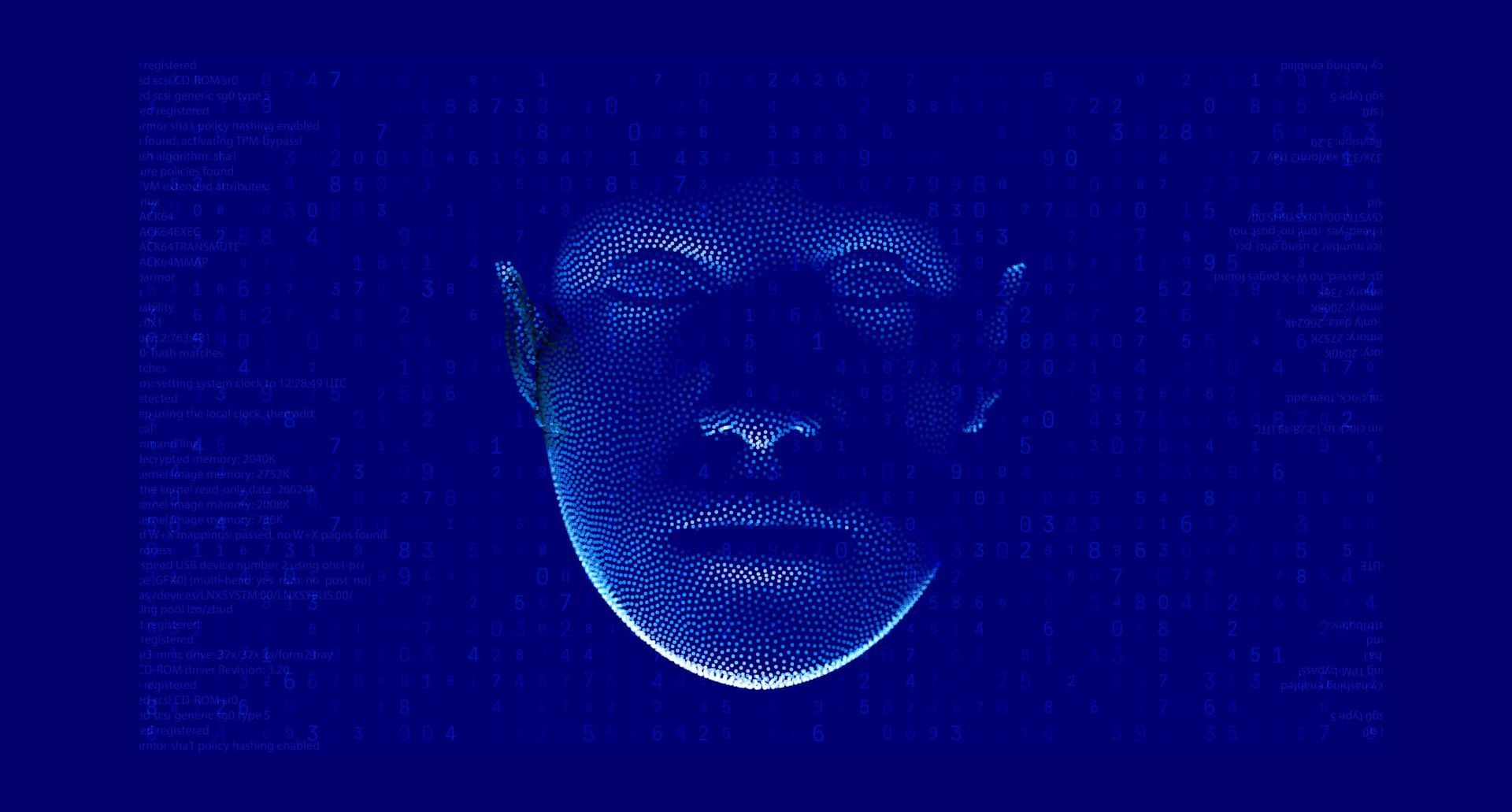

Just when I thought we had exhausted the possible universe of discussion topics about all the various and troubling ways that artificial intelligence technologies are promising to reshape the human experience (and rarely are these for the good) I come across another example that makes my head spin. This one is populated by what are called "deadbeats" being built by companies in what is coming to be known as the "digital-afterlife industry." There's a long article over at The Atlantic's website ( click here for a gift link to the story ) that goes into detail about the people and the companies developing the products that in some cases promise to make grief obsolete by giving users AI chatbot versions of deceased loved ones -- for a monthly subscription fee, of course. Or, in industry parlance, access to AI "deadbot" versions of those loved ones. And it seems that this is a lucrative technology. In 2024, the industry was valued at more than $22 billion, a sum expected to more than triple in less than 10 years. There are a lot of questions that emerge as we think about what all of this means for the way we experience grief and loss: "'Deadbots,' as these posthumous AI creations are known, promise to replace the dead, and the way they are remembered. This raises plenty of ethical issues, not least the extent to which turning deadbots into marketable products will rely on exploiting people in mourning. But perhaps the biggest question is how such a product might shift our experience of personal grief and collective memory. Is grief merely a painful human shortcoming that we haven’t learned to optimize our way out of yet, or does it have a purpose?" As the article makes clear, this technology is very different from the familiar ways we have come to memorialize those we have lost, whether through portraiture, literature, memoir, and so on, which are interpretive expressions of the living's memories of the dead. Instead, "Interactive griefbots are generative, producing “new utterances, new reactions, even new ‘memories’ and ‘behaviors,’ all under the guise of the deceased,” she said. This shift from representation to emulation presents a new ethical line, one that may require new legal protections. Both death and grief are states of profound vulnerability, she warned; the dead cannot stand up for their own interests, and the bereaved may not be in a psychological state to protect themselves from financial manipulation by a company incentivized to prolong their grief. One company, called You, Only Virtual, or YOV, says its point isn't to make grief easier, but rather to bypass it altogether. The company launched with the tagline, "Never have to say goodbye," and promises a user experience that will make you feel as if your loved one never died. In other words, they are promising not to capture every aspect of the person who has passed, but instead to capture how the user felt with that person when they were alive. The point of the interaction is "about inducing the emotions of the living, not imitating the emotions of the dead." We're going to talk about all of this in our conversation this week. Not just about the technology, but about grief itself, how we experience it, and what grief does to and for us. Read the article by clicking on the link above, then join us for the discussion this Tuesday, Feb. 3, starting at 7pm at Irish Tavern in downtown Lake Orion.

It has been our practice in recent years to try to build our discussion around the words of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. whenever our conversation falls around the celebration of his birthday. This seems especially appropriate this year given the events unfolding in Minneapolis and elsewhere since the start of the new year. This time we're going to focus on the idea referenced in our illustration above. This is often misquoted as "the arc of the universe ..." which leaves out King's important qualifier, the "moral," universe, not the universe more generally. Before we did deeper, what do you think is the key difference or differences between the two ideas, the universe generally vs. the moral universe? King used this quote many times in his sermons and speeches, and according to Stanford University historian Clayborn Carson , he borrowed it from 1850s abolitionist Theodore Parker. In fact, King drew quite heavily on the oratorical tradition of the early abolitionists, bringing their words and sentiments to bear in the 1960s struggle for civil rights. But what are they getting at here? Is the idea that while things may be bad now, if we wait long enough the scales will tilt to the side of justice? Or is it not that simple. What this little snippet of a quote does not do, is give any suggestion as to how the arc of the moral universe bends. Or what is required to make it do so. So what do you think? If the arc of the moral universe ultimately bends toward justice, by what mechanism or mechanisms does it do so? And what is our role in that process? Now that I think about it, this train of thought is kind of a continuation of something we landed on last week in our discussion of hope. James McGrath, a professor of New Testament language and literature at Butler University, addresses things this way: "The arc of the universe may bend towards justice, but it certainly does not do so in a steady and straight line. Precisely because of the slow but real progress ... the racists, misogynists, antisemites, Islamophobes, and homophobes are offering a backlash. Progress towards equality has always involved a process like this. It is important to emphasize that, because those of us who are living through this particular moment can feel like these are unprecedented times." Join us for the conversation this week as we talk about the arc of the moral universe and how it bends. And if this isn't a meaty enough topic, here's one more MLK quote that we can chat about if we have the time: "If any earthly institution or custom conflicts with God’s will, it is your Christian duty to oppose it. You must never allow the transitory, evanescent demands of man-made institutions to take precedence over the eternal demands of the Almighty God." The only trick here, of course, is figuring out what does and does not conflict with God's will, and who decides. Come out of the cold this Tuesday evening, Jan. 20, and let us know what you think. The discussion starts at 7pm at Irish Tavern in downtown Lake Orion.