Pub Theology 2/18/25 -- Is common sense enough?

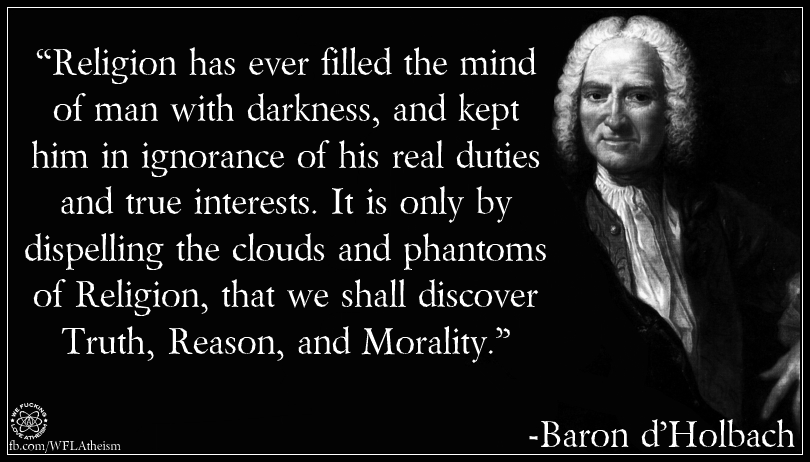

Indifference, if not outright hostility, toward religion is not just a feature of our current age, but has been around for quite a while. Humanists, secular philosophers, and atheists of many stripes have long tarred religion with the brush of superstition and ignorance. The quote above, from 18th century French Enlightenment philosopher and writer Paul Thiry Baron d'Holbach, comes out this tradition.

D'Holbach believed that people can use common sense to discover moral principles without needing religion or divine intervention. He thought that people should be just, moderate, and sociable because it makes them feel good, not because it's what a god commands. In his 1772 book Good Sense: or, Natural Ideas Opposed to Supernatural makes the following claim: "To discover the true principles of Morality, men have no need of theology, of revelation, or of gods: They have need only of common sense.”

At its heart, what d'Holbach puts forward is an alternative theory of the origins of morality. As an advocate of secular morality, and a self-described anti-theist and opponent or religion, d'Holbach and others who have adopted this perspective essentially argue that morality doesn't require religion. It's based on social ties, education, and sympathy. Some say that people shouldn't be motivated by the fear of punishment or the hope of reward after death. In contrast, those who approach morality through a theist lens, i.e. a belief in God (or gods), suggest that without God, morality would just be a social convention without any universal validity beyond cultures or self-interest.

The second chapter of the Epistle to Titus, traditionally attributed to St. Paul though the scholarly consensus casts significant doubt on that attribution today, is essentially guidance to clergy, specifically bishops, for the teaching of "sound doctrine," in other words instruction in what does and does not meet the demands of moral conduct. Titus 2:11-12 roots this in the divine: "For the grace of God has appeared for the salvation of all men, training us to renounce irreligion and worldly passions, and to live sober, upright, and godly lives in this world,"

Let's talk about this. Is common sense, and common sense alone, sufficient to produce morality, or, as the baron puts it, discover its true principles? Is d'Holbach right, is common sense enough? And if it is, why does it -- both common sense and morality -- seem is such short supply sometimes? Or is morality a consequence of divine authority?

Join us for the conversation this week as we wrestle with the age-old question of where morality comes from. The discussion starts at 7pm Tuesday, Feb. 18 at Casa Real in downtown Oxford.

Useful Links

Contact info

(248) 391-0663

office@stmarysinthehills.org

2512 Joslyn Court

Lake Orion, Michigan 48360

Join our community

Contact Us

We will get back to you as soon as possible

Please try again later